Oklahoma Wheat

Bread and Cereals

Of grasses farmers grow;

They're all ground up and mixed with eggs

And other flavors for dough.

And noodles of chicken soup,

Doughnuts, spaghetti, and Cream of Wheat

Are in the bread and cereals group

Wheat, oats, barley and other grains are grasses, but no one yet has found the wild form of grass from which wheat, as we know it, was developed. Hard red winter wheat is Oklahoma's number one crop and is very important to the Oklahoma economy. In 2015, 98.8 million bushels of wheat were harvested at a value of $489 million. Oklahoma ranks number three in the nation in the production of winter wheat. Hard red winter wheat is the kind of wheat used for making bread.

Most Oklahoma wheat producers grow winter wheat. Late in the summer, they prepare the soil for planting. They drive a tractor that pulls the plow through the fields. The plow turns the soil over and kills all the weeds. Then the farmer connects the tractor to a disk harrow and drives it over the field. The disk harrow breaks the soil down into smaller pieces. When the soil is ready for planting, the farmer uses a grain drill to plant the seed.

Disk Harrow

Disk Harrow

The wheat plant will grow about six inches before the frost comes. Each plant grows by producing more leaves and new stalks from the base of the plant. The new stalks are called "tillers." When the weather gets cold the tiller will stop growing. This is called the dormant period. On most farms in the Southern Plains, cattle feed, or graze, on the young wheat plants while they are in their dormant period. The plants grow back. They are not damaged by proper grazing.

In the spring, the warm moist days make the wheat plants grow quickly. As the wheat comes out of its dormant period, more tillers of wheat emerge. Each tiller can form another head of wheat. Some varieties of wheat grow as tall as seven feet, but most are only between two and four feet tall. During the early summer, the plants begin to fade from dark green to tan and then to a golden brown. Then the wheat is ripe and nearly ready for harvest. Now the wheat producer must race with the weather to get the wheat out of the fields.

Some years the wind and rain keep the plants from ripening, and they cannot be harvested. Other years hail may break all the heads, or a lightening storm may start a range fire. When the weather cooperates, and the wheat is ripe, the farmer must move fast. He checks the wheat by rubbing a wheat head between his hands, blowing the chaff away and then chewing some of the grain. If the kernels crack easily and get soft as they are chewed, the wheat is ready to harvest.

The farmer drives a combine across the fields to harvest the grain. When the storage bin of the combine is full, he empties it into a truck. Someone else drives the truck to the grain elevator in town. Workers at the grain elevator help empty the wheat into a very deep pit. Machinery in the grain elevator raises, or elevates, the wheat into a tall bin. In many small towns in Oklahoma, the grain elevator is the tallest building in the town.

The wheat stays in the grain elevator until the farmer is ready to sell it. Workers keep an eye on the wheat kernels to make sure they stay cool and dry. If the wheat kernels get wet or too hot they will spoil. Some of the wheat is sold to people who use it to make food for people and animals. The rest is cleaned and saved until it is time to plant again. One kernel of wheat can grow several hundred new kernels next harvest.

The wheat that is sold for food is taken to a mill. At the mill, huge machines grind the wheat kernels into flour. First the wheat must be cleaned several times. A series of disks separate the wheat kernels from weed seeds, dirt and small stones. A giant magnet removes any metal pieces, like nuts or rivets that might have shaken loose from the farm machinery and fallen in with the wheat. Finally the kernels go into a giant water bath where any remaining stones or other heavy materials drop to the bottom. Light materials float to the top and are washed away. Now the wheat is cleaned and ready to be milled.

Rollers crack the kernels into smaller pieces. Huge machines shake the wheat pieces through several screens to make the pieces even smaller. If the wheat is to be made into white flour, air currents blow the bran—the outer layer of the kernel — away from the rest of the wheat. The wheat bran and germ that have been removed are used in animal feeds. The pieces are now ready for grinding. Smooth rollers grind the wheat finer and finer. After grinding, the wheat is sifted through more screens, sometimes as many as 25 times. Each screen has smaller openings than the one before. Special ingredients are added to age the flour and whiten it. Vitamins and iron are also added to replace those that have been removed with the wheat germ and bran. Now the flour is ready for baking.

Bread

Bread may be the ancestor of all prepared foods. The first bread was made in Neolithic times, nearly 12,000 years ago. It was probably made by crushing grain and mixing it with water. The dough was then baked in the sun or laid on heated stones and covered with hot ashes. The Hopi of New Mexico still make a traditional bread, called "piki bread," by mixing juniper ash with cornmeal and spreading it on a hot stone. Then they lift the paper-thin layer from the stone by rolling it like a jelly roll.

Loaves and rolls made and baked over 5,000 years ago have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs, and wheat has been found in pits where human settlements flourished 8,000 years ago. In the Stone Age, people made solid cakes from stone-crushed barley and wheat. Wheat and other grains provided ancient people with a reliable food source which would keep through the winter months and multiply in the summer. This allowed them time to develop other useful skills beyond what they required to feed themselves.

Bread can be unleavened or leavened with yeast. When flour comes in contact with water and remains idle for a period of time, it begins to rise. In modern processes, yeast is added to aid in the rising, but even without yeast, dough will begin to ferment, and the resulting gases will cause the dough to rise. The Egyptians were the first to discover that this process would produce a light, expanded loaf. The Egyptians also invented a closed oven in which to bake the bread.

The ancient Hebrews were in such a hurry to get away from their Egyptian captors that they made their bread without leavening. Today Jewish people celebrate Passover, their escape from the Egyptians, with unleavened bread—matzo. Bread without leavening also represents truth in Jewish tradition, because bread that is unleavened retains the true flavor of the grain from which it is made.

Traditionally, people made bread from whatever grain grew best in the area where they lived. Wheat, rye, corn, barley, millet, kamut and spelt are some of the grains used around the world. Wheat flour is preferred because of its gluten content. Gluten is what gives bread its elastic quality.

Bread is such a powerful food that ancient Egyptian governments controlled its production and distribution as a way to control the people. In France the shortage of bread helped start the French Revolution.

A millstone used for grinding grain has been found that is thought to be 7,500 years old. For thousands of years people used stone wheels powered by wind to grind wheat into flour for bread. In the middle of the nineteenth century, a Swiss engineer invented a new type of mill with rollers made of steel which operated one above the other and were driven by steam-engines. Meanwhile, the North American prairies were found to be ideally suited to grow wheat. This, together with the invention of the roller-milling system, meant that for the first time in history, whiter flour (and therefore bread) could be produced at a price which brought it within the reach of everyone— not just the rich.

Wheat came to our continent with European settlers. Before that, maize was the grain used for bread-making in the Americans. Maize is what we now call corn, but the word "corn" actually means any kind of grain. For centuries, maize was used to make a flat bread that we know as tortillas. According to Mayan legend, tortillas were invented by a peasant for his hungry king. The first tortillas were made over 12,000 years ago. Today they are also made with wheat.

Among native Mexicans, tortillas are commonly used as eating utensils. In the Old West, cowpokes realized the versatility of tortillas and used tortillas filled with meat or other foods as a convenient way to eat around the campfire.

Flour tortillas are a low-fat food and contain iron along with other B vitamins. They have about 115 calories with 2-3 grams of fat per serving. Corn tortillas are a low-fat, low-sodium food and contain calcium, potassium and fiber. An average serving contains about 60 calories with 1 gram of fat.

Both whole wheat flour and all-purpose (white) flour are made from kernels of wheat. A wheat kernel is divided into three major parts—bran, endosperm and germ. All-purpose flour is made from only ground endosperm. Whole wheat flour is made by grinding the entire wheat kernel. When shopping for 100 percent whole wheat bread, look for a label that has the words "whole wheat."

Enriched white bread has about the same nutrients as whole wheat bread. Both are excellent sources of carbohydrates, fiber, protein, B-vitamins and important trace minerals. Whole wheat bread contains 5.3 percent dietary fiber, while white bread has only 1.6 percent. Scientists tell us that an adequate amount of fiber in our diet may help prevent certain types of cancer. Fiber is found in mainly whole grain breads and cereals and in fresh fruits and vegetables.

Learning Activities

Oklahoma State Department of Education

Child Nutrition Department

Becky Gray, Child Nutrition Coordinator

Room 310

405.522.5042

- Smart Board Activity: Pasta Poetry

(Need help?)Please be patient with us as we learn how to use this new technology.

You must have Smart Notebook software installed on your computer to open Smart Board activities. If you have Smart Notebook software and are using Internet Explorer, you may get a message telling you the activity cannot be opened. In this event, save the activity to your hard drive. Your browser will save it as a zip file. Simply change the "zip" in the file name to "notebook," and you should be able to open it.

Thank you for your patience.

Smart Board Acitivity page

Red Dirt Groundbreakers: AC Magruder and the Magruder Plots

Red Dirt Groundbreakers: AC Magruder and the Magruder Plots

The man who planted the experimental Magruder Plots, the oldest continually-producing wheat plots west of the Mississippi.

Additional Resources

- Oklahoma Wheat Harvest (Sunup)

- More Facts about Wheat

- Books

- Wheat Berry Sprouts

- Wheat Kernels: Quick ideas for teaching about wheat

- Bread and Grain Recipes

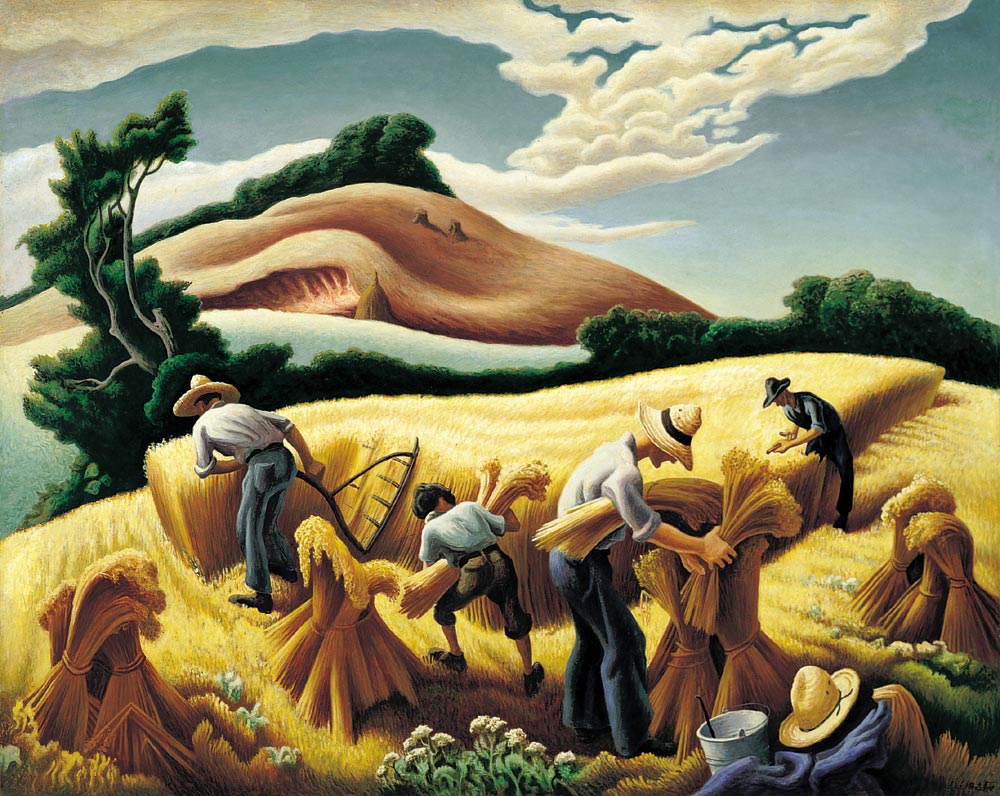

- Agriculture in Art

- Thomas Hart Benton

- Cradling Wheat, 1938 (St. Louis Art Museum)

- Threshing Wheat, 1939

- Wheat, 1967

- In the Wheat Fields at Gennevillers, 1875 by Berthe Morisot

- Vincent Van Gogh

Cradling Wheat, 1938 by Thomas Hart Benton (St. Louis Art Museum)

Rain

Just for Fun

Image Credit: Adam Ellis, Buzz Feed

Image Credit: Adam Ellis, Buzz Feed