Alfalfa, Hay and Silage

Hay

Before there were cars, trucks and farm equipment, it was workhorses that provided transportation and helped with work on the farm and in other industries. Hay was the fuel that made the horses go. Farmers needed huge quantities of hay for their cattle and their sheep. Horses were also used in the mining, lumbering, and road building industries. Horse used for hauling and personal transportation in cities needed fodder, too. Farmers put up hay for their own use and sold the extra in local markets or baled it and shipped it to markets farther away.

Haymaking involved cutting, gathering, drying and storing grasses or legumes, like alfalfa or clover. Hay was best made during late June, July and August. First the hay was cut with a scythe or a mower. Then sun and wind dried the hay as it lay in the field. When the moisture content was low enough, the hay was raked up and stored in stacks in the field or loaded on a hay rack or elevator (conveyor) and hauled to the yard. Here it could be stored in stacks or in the mow (loft) of a barn. The loose hay would continue to dry in the mow and was fed out by pitching it down to the animals below.

Most haymaking was done by family members, male and female, working with neighbors and casual help. Hired men usually got the heavy work, such as pitching hay or building stacks. Women and older children often did the raking and drove the teams of horses. Smaller children brought lunches and cold drinks to the hayfield.

Farmers today still need hay to feed their animals, but now machinery does much of the work. Most hay is now baled in huge round bales, usually by just one person. Round balers produce bales weighing 600-2000 pounds. The bales are either left in the field until they are used or moved to a covered storage area.

Oklahoma has excellent conditions for growing hay, which requires plenty of rain, and then hot dry weather for harvest. In 2015, hay ranked number four of all the state's agricultural commodities. Some of the premium alfalfa hay goes to feed the state's large equine (horse) population.

Common plants used for making hay in Oklahoma are alfalfa, wild and prairie grasses, sorghum/sudan crosses, sudan, Bermuda, lespedeza, soybean, peanut, and small grains like wheat, rye and oats. Many people confuse hay with straw. The square bales often sold in the fall for Halloween decorations are actually bales of straw. Straw is the stubble that is left after the grains from plants like wheat, oats and rye are threshed from the plant. It is most commonly used in animal bedding, as mulch for gardens and, in some cases, even in the walls of houses.

Alfalfa

The best hay is made from alfalfa. Its name in Arabic means "the best fodder." Alfalfa originated in southwest Asia and is believed to have been first cultivated in Iran. It was introduced into Greece as early as 490 BC as food for chariot horses. Both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew alfalfa.

Alfalfa can grow in many different climates and can tolerate a variety of soil conditions. Alfalfa is usually planted in April or May. It is a perennial crop, which means it will grow in the same field four or five years in a row without replanting. Farmers like alfalfa because it is a legume plant which captures nitrogen to enrich the soil. Nitrogen is food for the soil and helps feed other plants which may be grown later in the same field.

The alfalfa plant is harvested at least three times each summer—in June, July and August. The alfalfa plant grows two to three feet tall and is cut before it produces flowers. Much of the alfalfa hay grown in Oklahoma is produced for feeding horses.

Silage

Silage is preserved pasture. It is high-moisture feed for livestock that is made from crops fermented without air and can be stored over winter. It is pasturre grass that has been pickled. Making silage is an important way for farmers to feed cows and sheep during times when pasture isn't good, such as the dry season.

To make silage, the grasses are cut and then fermented to keep as much of the nutrients (such as sugars and proteins) as possible. The fermentation is carried out by microscopic organisms living in the grass.

The process must be carried out under acidic conditions (around pH 4-5) in order to keep nutrients and provide a form of food that cows and sheep will like to eat. Fermentation at higher pH results in silage that has a bad taste, and lower amounts of sugars and proteins.

First, the pasture must be cut when the grasses contain their highest nutrient levels. This is usually just before they are fully mature. This is important because all forms of preserved grass, such as hay and silage, will have lower amounts of nutrients than fresh pasture, so everything must be done to make the end product as nutritious as possible.

After the grass is cut it is left to wilt in the field for a few hours to reduce the moisture content to around 60-75%. This moisture level will allow for optimum fermentation. If the grass is left out longer, it may get too dry, or it may get rained on - and both these will reduce proper fermentation. Also, the longer the grass is left uncut, the higher the loss of nutrients.

The cut grass is chopped into even smaller pieces and then compacted to remove as much oxygen as possible. (This is important because the microorganisms needed to carry out the fermentation like living in oxygen-free environments). If the silage is to be stored in a large pit, tractors and other machinery are usually driven over the grass pile until it is firm. If the silage is stored as bales, the baling machines will compact the grass as they work. The next step is to seal the compacted grass with plastic to keep oxygen out. Mounds of silage are covered with huge polythene (plastic) sheets and weighted down (usually with old tyres) to ensure maximum compacting; bales are covered with a plastic wrapping.

While oxygen remains, plant enzymes and other bacteria and microorganisms react with the plant sugars and proteins to make energy, reducing the amounts of these nutrients in the grass.

Once all of the oxygen is used up, lactic acid bacteria start to multiply. These are bacteria that are needed to make the silage, and they turn the plant sugars into lactic acid. This causes the pH to drop (the mixture because more acidic). Once the pH is around 4-5, the sugars stop breaking down and the grass is preserved until the silage is opened and exposed to oxygen.

If the pH isn't low enough, a different kind of bacteria will start fermenting the silage, producing by-products (like ammonia) that taste bad to cows and sheep.

Learning Activities

Additional Resources

- More Facts about Hay and Silage

- Agriculture in Art

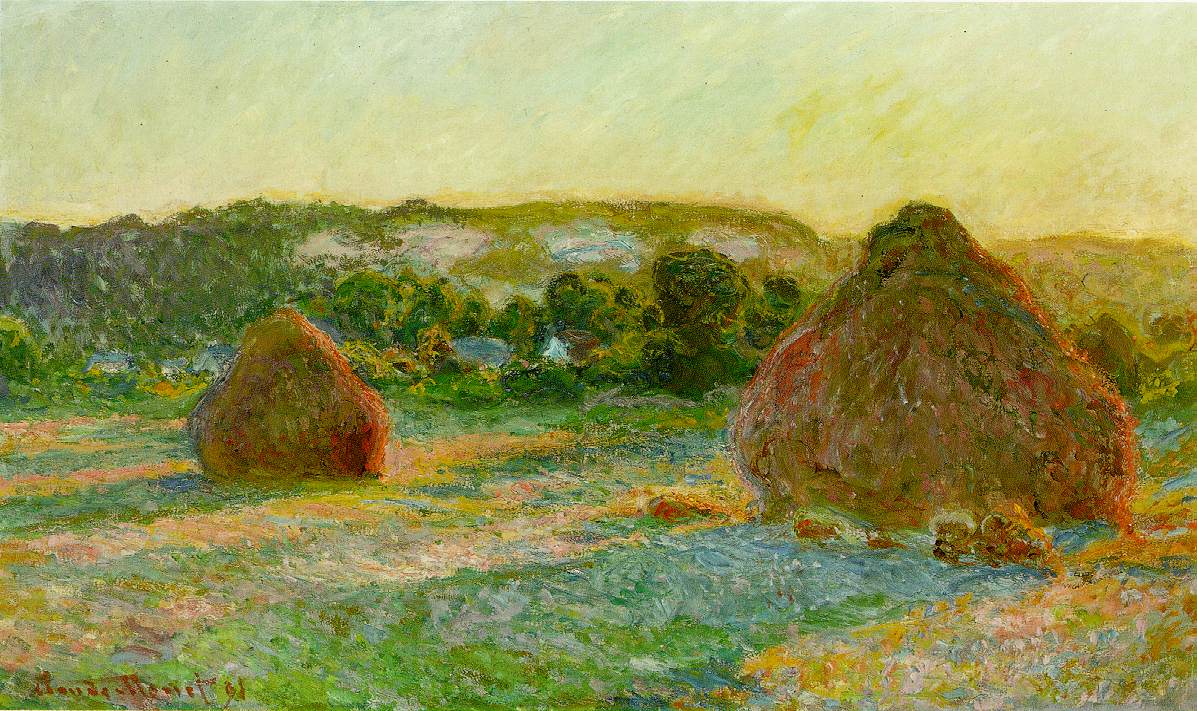

- Haystacks by Claude Monet

Click on the link above to show students some examples of paintings of hayfields. Ask students why hay fields would be a popular subject for artists. Compare the treatment by different artists. How are they different? How are they the same. If possible, get prints of Claude Monet's series of paintings of haystacks to show students and discuss why Monet painted the same scene over and over again. How are the paintings different? How are they the same? - Die Heuerente (Hay Harvest), 1855 by Ford Maddox Brown

- Haymaking in Brittany, 1888 by Paul Gaugin

- Haymaking, 1565 by Pieter Brueghel the Elder

Haystacks, Claude Monet

Haystacks, Claude Monet